Covid and ocular surface disease

In February of 2021, a 42-year-old woman was referred to our ocular surface disease clinic with ongoing symptoms of dry eye following her SARSCoV2 (Covid) infection in late 2019, which she had contracted in Hong Kong and had made her quite unwell.

After recovering, when all her other symptoms had resolved, she still complained of marked ocular discomfort and dry eyes. Blood tests for the most likely causes, including Sjögren syndrome, were all negative. On examination she exhibited both aqueous tear deficiency and marked meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), though, unfortunately, we had no baseline to compare this with.

MGD is very common, especially in women and with increasing age; however, the abruptness and severity of this patient’s symptoms got me thinking about the ocular side effects of Covid. We have all seen increasing numbers of patients with dry eye symptoms since the start of the pandemic. Many of these patients are in their twenties to forties. There can be many reasons for their symptoms, including increased device use and the use of face masks, especially ill-fitting ones, sometimes referred to as mask-associated dry eye (MADE)1.

A meta-analysis by Nasiri et al of more than 38 studies involving 8,219 patients, found that around 11% of patients reported ocular symptoms post-Covid infection. Of these, 16% reported dry eye and foreign body sensation. Ocular redness and itching were also reported2. Various studies have shown neurological symptoms such as fatigue, anosmia, ageusia, chronic fatigue and respiratory issues persist in many people post-infection. Studies involving the neurotropic effects of the virus are ongoing, but its effects on the central nervous system are well documented3,4,5.

Research into Covid-19 shows the virus binds to ACE2 receptors in host cells6,7. We know the cornea is the most densely innervated tissue in the body, with around 7,000 nociceptors per mm² in the central cornea and dropping off towards the periphery8. The nerves originate from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve and are responsible for maintaining corneal integrity and homeostasis, all have ACE2 receptors, making them susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Changes to the structure and function of nerves induces pain and neuropathies, with some of these effects being long-lasting9,10.

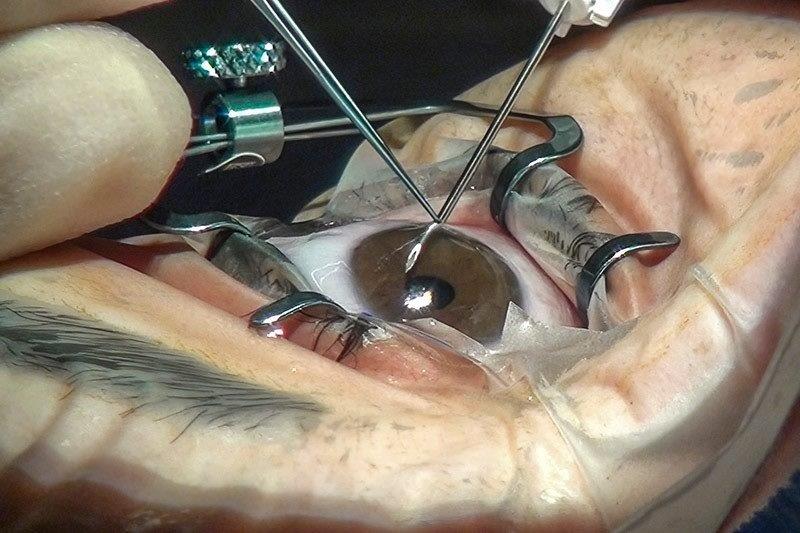

Research using confocal microscopy has highlighted changes in the corneal subbasal nerve plexus of patients post-SARS-CoV-2 infection, similar to the corneal changes observed in patients with diabetes and in patients with dry eye disease (DED).

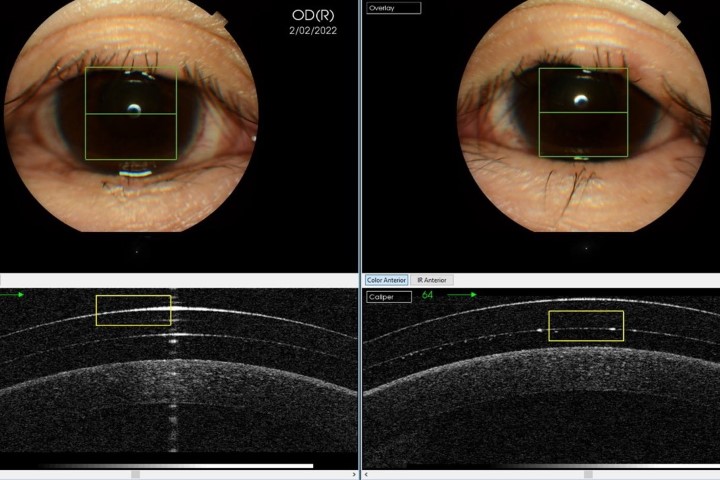

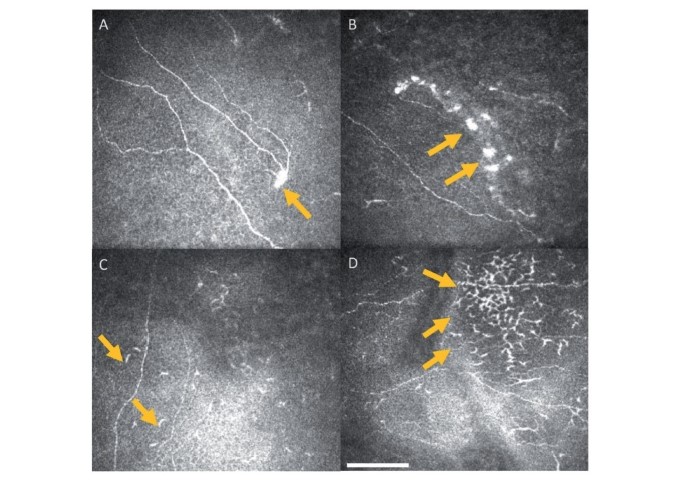

In one study by Barros et al, 91% of participants presented with alterations to their corneal subbasal plexus and corneal tissue consistent with small fibre neuropathy, including beaded axons, neuroma-like images and dendritic cells11. Another study found dendritic cells appeared to be increased in patients with neurological symptoms post-Covid infection and suggested in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) might prove useful in identifying patients with long-Covid12 (see Fig 1). These morphological changes are often evident months after recovery from the virus and have been shown to be associated with changes in nerve sensitivity13,14.

Fig 1. Central corneal IVCM images. Arrows highlight neuromas (A,B) and dendritic cells (C,D)

In examining patients with dry eye symptoms, we often ask about device use, regular medications used and exposure to air conditioning, among other things. While a confocal microscope may not be readily at hand to assess corneal morphology in most practices, it is worth bearing in mind that previous SARS-CoV-2 infection may be a contributing factor when assessing patients presenting with DED symptoms.

References

- Krolo I, Blazeka M, Merdso I, Vrtar I, Sabol I, Petric-Vickovic I. Mask-associated dry eye during Covid-19 pandemic: how face masks contribute to dry eye disease symptoms. Med Arch 2021 Apr; 75(2):144-148

- Nasiri N, Sharifi H, Bazrafshan A, Noori A, Karamouzian M and Sharifi A. Ocular manifestations of Covid-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2021 Jan-Mar; 16(1):103-112

- Payus A, Liew Sat Lin C, Mohd Noh M, Jeffree M, Ali R. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the nervous system: a review of the literature on neurological involvement in novel coronavirus disease. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2020;20:283–292

- Som Chaudhury S, Sinha K, Majumder R, Biswas A, Das Mukhopadhyay C. Covid-19 and central nervous system interplay: a big picture beyond clinical manifestation. J Biosci. 2021; 46(2): 47

- Berger J. Covid-19 and the nervous system. J Neurovirol. 2020;26:143–148

- Shang J, Ye G, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H, Geng H, Auerbach A, Li F. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 581, 221-224 (2020)

- Scialo F, Daniele A, Amato F, Pastore L, Gabriella Matera M, Cazzola M, Castaldo G and Bianco A. ACE2: The major cell entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung. 2020; 198(6): 867-877

- Muller L, Marfurt C, Kruse F and Tervo T. Corneal nerves: structure, contents and function. Exp Eye Res 76, 521–542 (2003)

- McFarland A, Yousuf M, Shiers S, Price T. Neurobiology of SARS-CoV-2 interaction with the peripheral nervous system: implications for COVID-19 and pain. Pain Rep. 2021 Jan 7;6(1):e885

- Shiers S, Ray P, Wangzhou A, Sankaranarayanan I, Esteves Tatsui C, Rhines L, Li Y, Uhelski M, Dougherty P, Price T. ACE2 and SCARF expression in human dorsal root ganglion nociceptors: implications for SARS-CoV-2 virus neurological effects. Pain. 2020 Nov;161(11):2494-2501

- Barros A, Queiruga-Pineiro J, Lozano Sanroma J et al. Small fibre neuropathy in the cornea of Covid-19 patients associated with the generation of ocular surface disease. Ocul Surf. Jan 2022; 23:40-48

- Bitirgen G, Korkmaz C, Zamani A, Ozkagnici A, Zengin N, Ponirakis G and Malik R. Corneal confocal microscopy identifies corneal nerve fibre loss and increased dendritic cells in patients with long Covid. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106:1635-1641

- Midena E, Cosmo E, Cattelan A, Briani C, Leoni D, Capizzi A, Tabacchi V, Parrozzani R, Midena G and Frizziero L. Small fibre peripheral alterations following Covid-19 detected by corneal confocal microscopy. J Pers Med. 2022 Apr; 12(4):563

- Wan K, Lui G et al. Ocular surface disturbance in patients after acute Covid-19. Clin Exp Optom. May 2022; 50(4):359-470

Wendy Hill is an optometrist based at Mortimer Hirst and Eye Institute in Auckland.