DMO: looking beyond HbA1c

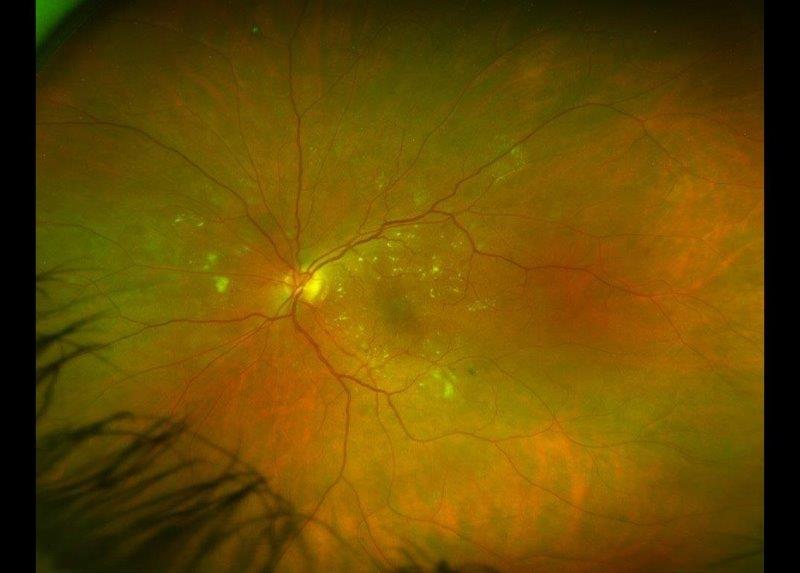

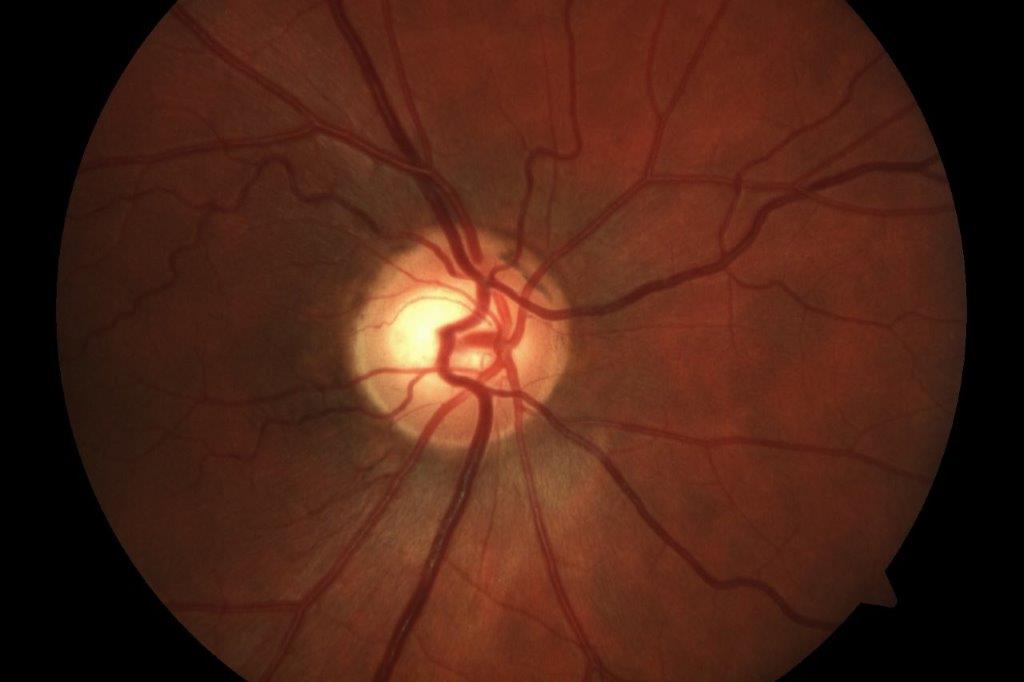

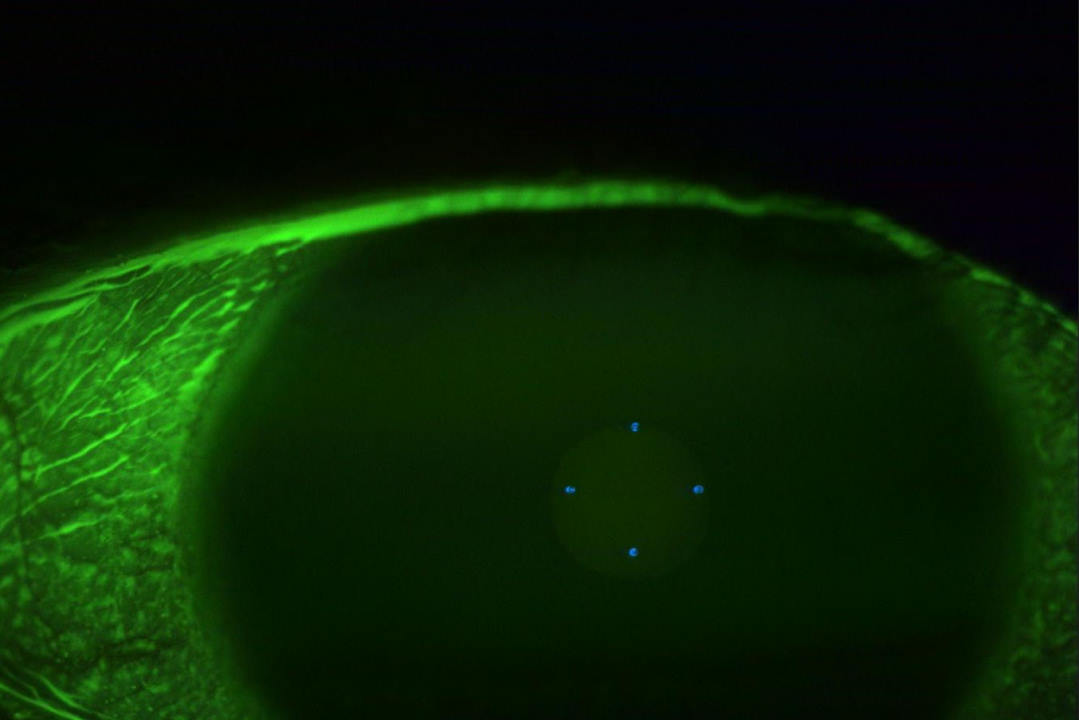

Diabetic macular oedema (DMO) is a common complication of diabetic retinopathy (DR) and a leading cause of vision impairment¹. It is characterised by the accumulation of fluid in the macula, resulting from the rupture of the retinal barrier. The integrity of the retinal barrier is compromised by hyperglycaemia-induced microvascular damage and activation of inflammatory pathways². DMO can occur at any stage of retinopathy, but the prevalence tends to increase as a patient’s duration of diabetes and severity of DR increases¹.

Intravitreal anti-VEGF injections and laser therapy are the mainstay of current therapies used to stabilise and prolong visual acuity. However, not all DMO requires treatment. A recent randomised controlled trial³ showed patients with centre-involved DMO and visual acuity of 6/7.5 or better can be safely observed. Thus, identifying risk factors associated with the development and worsening of DMO is key to ensuring a timely diagnosis and adopting an appropriate treatment plan.

Most ophthalmologists believe that glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) plays a significant role in the development of DMO. However, current research has begun to challenge the previously held belief that elevated HbA1c has a predictive role in DMO pathology or treatment outcomes⁴. A post-hoc analysis of the phase 3 Panorama trial examined 638 baseline systemic and ocular factors to determine their association with worsening non-proliferative DR and/or the development of DMO⁵. Of all the factors, including HbA1c, only larger fluorescein leakage and retinal nonperfusion areas at baseline were associated with an increased risk of DMO at week 100⁵.

Similar results were seen in a post-hoc secondary analysis of the DRCR Retina Network Protocol V study, which assessed the treatment regimen of initial observation with initiation of aflibercept only if visual acuity worsened in patients with centre-involved DMO. The analysis examined whether select baseline characteristics within the initial observation group were associated with receiving aflibercept injections during the two-year follow-up. Interestingly, the analysis found HbA1c levels did not have an effect on the need for treatment in the initial observation group. This adds weight to the notion that HbA1c levels are not predictive of DMO worsening⁶. In addition, a growing body of evidence reports that HbA1c is not predictive of anti-VEGF treatment efficacy for patients with DMO. A recent retrospective analysis of 178 eyes treated with anti-VEGF therapy found changes in visual and anatomic outcomes were independent of HbA1c and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) values⁷.

If HbA1c and glycaemic control are not driving DMO, what is?

Recently, diabetic nephropathy, specifically albuminuria, has been found to be associated with the development of DMO⁸. In a retrospective case series of 261 patients with type 2 diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), diabetes duration and the presence of albuminuria were all significantly associated with the development of DMO⁹. A further large-scale eight-year cohort study of 2,135 Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes found that a serum albumin to creatinine ratio of >30mg/g was strongly predictive of DMO development⁸. There is also evidence associating high albuminuria and the presence of subretinal fluid in DMO patients and low serum albumin with increased subretinal fluid thickness¹⁰. The evidence of eGFR as a potential biomarker is mixed and less convincing⁸,¹¹.

It is also worth noting that haemodialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease has been shown to reduce central retinal thickness and improve best-corrected visual acuity in 93.2% of study eyes with DMO in the 12 months after haemodialysis initiation¹². The authors proposed that haemodialysis may have improved the flow of excess fluid between the retina and the choroidal tissue or the retinal pigment epithelium, lending weight to the idea that DMO pathophysiology is driven in part by oncotic or osmotic pressure changes increasing vascular permeability¹².

This may also explain the lack of an association between high HbA1c and DMO. Lower HbA1c can increase subretinal fluid and central macular thickness in DMO – possibly driven by low serum glucose levels reducing intravascular osmotic pressure – leading to fluid moving from the intravascular to the subretinal space¹⁰.

Implication for clinical practice

In the past, I only considered the level of HbA1c to determine the risk of development or progression of DMO when I saw a diabetic patient. Now, although I still look at HbA1c, I will also evaluate urine microalbumin, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and serum albumin to help me decide if a patient is likely to develop vision-threatening DMO and if anti-VEGF treatment needs to be started.

Furthermore, the association between DMO and urine albumin loss raises the question of whether therapy to reduce urine protein loss in diabetic nephropathy may improve DMO. Potentially, if a treatment is available to reduce urine protein loss in diabetic nephropathy, it may also have a beneficial effect on DMO. Currently, an angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker is used in patients with diabetic nephropathy, but there is no strong evidence that these medications have a significant effect on DMO.

Lastly, some of my patients with DMO have good HbA1c while others had suboptimal HbA1c but managed to improve their glycaemic control over time. However, many of these patients are disappointed that their DMO does not improve, despite an improvement in glycaemic control. I now inform these patients that further tightening of an already good HbA1c is unlikely to help with DMO, but early involvement of a renal physician and an endocrinologist to optimise the treatment of diabetic nephropathy could prove beneficial.

References

- Girach A, Lund-Andersen H. Diabetic macular oedema: a clinical overview. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(1):88–97.

- Bahrami B, Zhu M, Hong T, et al. Diabetic macular oedema: pathophysiology, management challenges and treatment resistance. Diabetologia. 2016;59(8):1594–608.

- Baker C, Glassman A, Beaulieu W, et al for the DRCR Retina Network. Effect of initial management with aflibercept vs laser photocoagulation vs observation on vision loss among patients with diabetic macular edema involving the center of the macula and good visual acuity: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(19):1880–1894.

- Diep T, Tsui I. Risk factors associated with diabetic macular edema. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100(3):298–305.

- Wykoff C, Do D, Goldberg R et al. Ocular and systemic risk factors for disease worsening among patients with NPDR: Post Hoc Analysis of the PANORAMA Trial. Ophthalmol Retina. 2023.

- Glassman A, Baker C, Beaulieu W, et al. Assessment of the DRCR Retina Network approach to management with initial observation for eyes with center-involved diabetic macular edema and good visual acuity: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(4):341–349.

- Debourdeau E, Medard R, Chamard C, et al. for Fight Retinal Blindness! study group. Does HbA1c level or glomerular filtration rate affect the clinical response to endothelial growth factor therapy (ranibizumab or aflibercept) in diabetic macular edema? A real-life experience. Ophthalmol Ther. 2023;12(5):2657–2670.

- Hsieh Y, Tsai M, Tu S, et al. Association of abnormal renal profiles and proliferative diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema in an Asian population with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(1):68–74.

- Suzuki Y, Kiyosawa M. Relationship between diabetic nephropathy and development of diabetic macular edema in addition to diabetic retinopathy. Biomedicines. 2023;11(5):1502.

- Zhang X, Hao X, Wang L, et al. Association of abnormal renal profiles with subretinal fluid in diabetic macular edema. J Ophthalmol. 2022;2022:5581679.

- Temkar S, Karuppaiah N, Takkar B, et al. Impact of estimated glomerular filtration rate on diabetic macular edema. Int Ophthalmol. 2018;38(3):1043–1050.

- Takamura Y, Matsumura T, Ohkoshi K, et al. Functional and anatomical changes in diabetic macular edema after hemodialysis initiation: One-year follow-up multicenter study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7788.

The author would like to acknowledge Emma Donadieu for the development of the first draft of this article.

Dr Leo Sheck specialises in medical retina, genetic eye disease, electrodiagnostics for complex retina and optic nerve diseases and cataract surgery, especially with co-existing retinal diseases. He consults for Te Whatu Ora Auckland and Retina Specialists and is chair of the NZ Save Sight Society.