Dry eye and refractive surgery

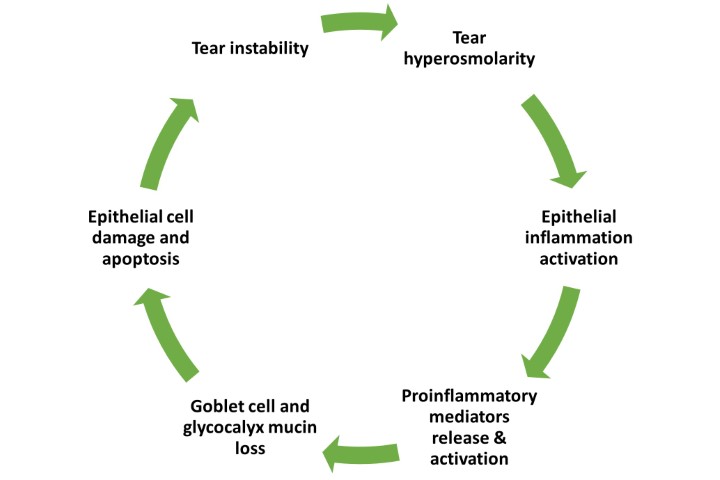

According to the TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification report, “Dry eye is a common multifactorial disease of the ocular surface, characterised by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film and accompanied by ocular symptoms in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play aetiological roles”¹. It can lead to a variety of symptoms including discomfort, light sensitivity and secondary reflex tearing, as well as anxiety and depression. Symptoms can fluctuate and the condition can affect patients' quality of life significantly².

Patients often have normal visual acuity with conventional testing methods, but more advanced tests may show abnormalities, such as increased optical aberrations and decreased corneal sensitivity. Su et al analysed the tear film objective scatter, a measure used to quantify ocular transparency index (TF-OSI), in dry eye disease (DED) patients³. The mean value and dispersion of TF-OSI were higher in patients with dry eye than in healthy subjects.

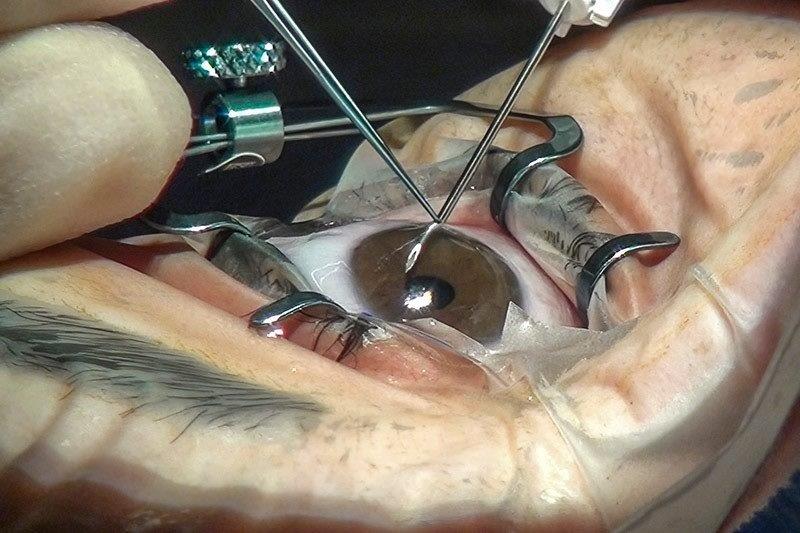

Patients presenting for laser refractive surgery require significant workup of their ocular surface as the surgery can exacerbate dry eye symptoms due to:

- Damage to the corneal afferent nerves with resultant hypoesthesia

- Reduced tear production

- Variation in the distribution of tears secondary to changes in corneal contour

- Inflammation induced by altered levels of cytokines

- Reduced blink rate

- Loss of conjunctival goblet cells

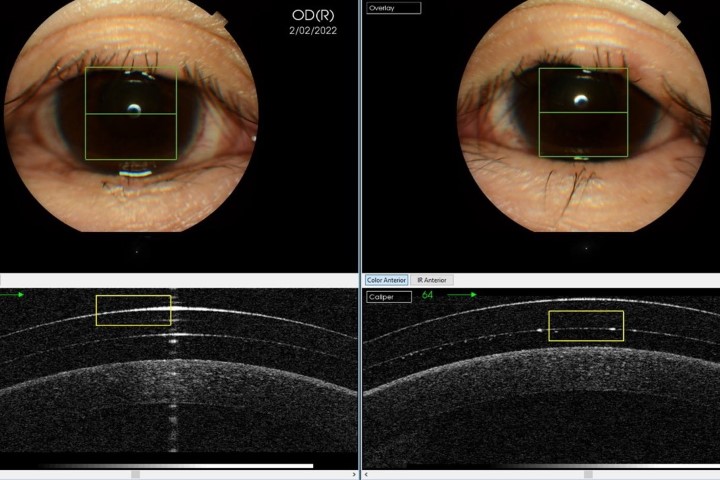

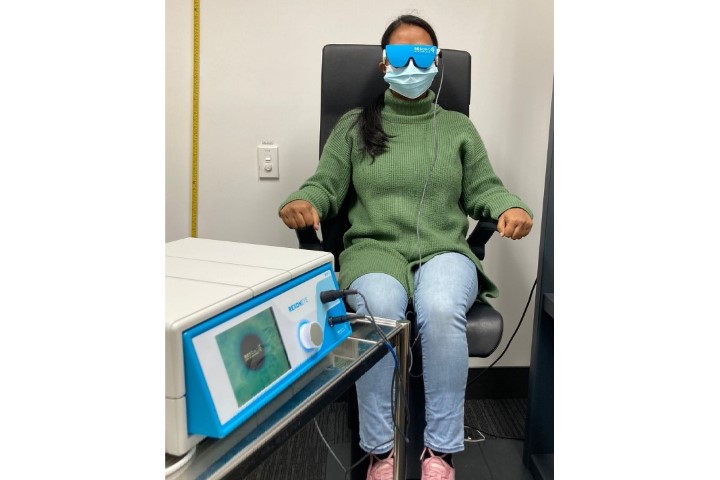

Some studies have reported that up to 95% of patients experience dry eye symptoms after laser refractive surgery. Symptoms usually improve with time and around 10% have symptoms at six months. It is important to emphasise that while symptoms usually last no more than a few months postoperatively for most, a few patients experience discomfort for more than a year after the procedure. For this reason, the ocular surface needs to be assessed carefully in the preoperative period to ensure patients are advised correctly regarding their risk profile and the anticipated recovery process. A careful history – potentially coupled with a patient questionnaire, as well as a careful examination of the lid and ocular surface – can identify those at risk of significant issues after laser refractive surgery. The exam is typically completed with ocular surface staining and tear break up time, but in borderline cases the surgeon may also complete a Schirmer test, NIBUT (non-invasive break-up time) and meibography to better assess the potential impact of laser vision correction on the ocular surface. Tests such as tear osmolarity and biomarker assessment are used only on rare occasions if the ocular surface is significantly compromised or if the patient has many risk factors for issues after surgery. Such risk factors include:

- Schirmer test value of less than 10mm before surgery

- Significant ocular surface staining

- Low corneal sensation

- Pre-existing DED symptoms before refractive surgery

- High degree of myopic refractive correction (>9D)

- Female sex

- Asian ethnicity

- Long-term contact lens use

If patients have multiple risk factors, they are usually advised to consider non-laser-based refractive procedures, such as implantable collamer lenses or refractive lens exchange. While there is some evidence that DED issues are more limited with certain types of laser refractive surgery, this is typically seen only in the early postoperative period. In a meta-analysis, corneal sensitivity was shown to be worse in LASIK compared to SMILE up to three months after surgery; however, after six months, sensitivity was similar in both groups⁴. Another study compared DED symptoms and signs following SMILE and LASIK and found SMILE produced less DED than LASIK at six months postoperatively, although after 12 months results were not very different⁵. In another meta-analysis, SMILE did not show obvious superiority over LASIK by exhibiting similar and acceptable objective parameters⁶. This topic is still debated, however, as there are other reports such as the recent TFOS Lifestyle Workshop publication which concludes that “SMILE refractive surgery seems to cause more vision disturbances than LASIK in the first month post-surgery, but less dry eye symptoms in long-term follow up”⁷.

The importance of co-management

While several studies have reported no significant difference in refractive outcomes in patients undergoing laser vision correction with pre- or postoperative dry eyes, the condition can substantially affect a patient’s perception of their refractive surgery process and their level of satisfaction⁸. Optometrists play an integral role in optimising outcomes as they can provide patient education and begin the treatment process before referral. Optometrists are also much better placed to start early treatment for pre-existing conditions such as meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), which will ultimately lead to a better ocular surface and better outcomes. Patients who are told about the importance of the ocular surface and possible longer period of recovery will be in a better position to comprehend the advice and comply with treatment. Co-management is becoming the norm in patient care, with pre- and post-surgical ocular surface treatment increasingly managed by optometrists. This growing collaboration between optometry and ophthalmology will lead to improved patient outcomes, overall satisfaction rates and ultimately a better overall patient experience.

References

- Craig J, Nichols K, Akpek E, Caffery B, Dua H, Joo C, Liu Z, Nelson J, Nichols J, Tsubota K, Stapleton F. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):276-283.

- Schiffman R, Walt J, Jacobsen G et al. (2003) Utility assessment among patients with dry eye disease. Ophthalmol. 2003 Jul;110(7):1412-1419.

- Su Y, Liang Q, Wang N, Antoine L. A study on the diagnostic value of tear film objective scatter index in dry eye. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2017 Sep 11;53(9):668-674

- He M, Huang W, Zhong X. Central corneal sensitivity after small incision lenticule extraction versus femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK for myopia: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;Oct 24;15:141.

- Wang B, Naidu R, Chu R, Dai J, Qu X, Zhou H. Dry eye disease following refractive surgery: a 12-month follow-up of SMILE versus FS-LASIK in high myopia. Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:132417

- Shen Z, Zhu Y, Song X, Yan J, Yao K. Dry eye after small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) versus femtosecond laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (FS-LASIK) for Myopia: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016 Dec 16;11(12):e0168081

- Gomes J, Azar D, Baudouin C, Bitton E, Chen W, Hafezi F, Hamrah P, Hogg R, Horwath-Winter J, Kontadakis G, Mehta J, Messmer E, Perez V, Zadok D, Willcox M. TFOS Lifestyle: Impact of elective medications and procedures on the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2023 Apr 20;29:331-385

- Shtein R. Post-LASIK dry eye. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2011 Oct;6(5):575-582

Dr Mo Ziaei is a consultant ophthalmologist specialising in cataract surgery, laser vision correction and corneal transplantation at Greenlane Clinical Centre and Re:Vision in Auckland. He is also a senior lecturer in ophthalmology at the University of Auckland.